Enhancing Mailer Targeting Accuracy Using ML

Table of contents

- 00. Project Overview

- 01. Data Overview

- 02. Modelling Overview

- 03. Logistic Regression

- 04. Decision Tree

- 05. Random Forest

- 06. KNN

- 07. Modelling Summary

- 08. Application

- 09. Growth & Next Steps

Project Overview

Context

Our client, a grocery retailer, sent out mailers in a marketing campaign for their new delivery club. This cost customers $100 per year for membership, and offered free grocery deliveries, rather than the normal cost of $10 per delivery.

For this, they sent mailers to their entire customer base (apart from a control group) but this proved expensive. For the next batch of communications, they would like to save costs by only mailing customers that were likely to sign up.

Based upon the results of the last campaign and the customer data available, we will look to understand the probability of customers signing up for the delivery club. This would allow the client to mail a more targeted selection of customers, lowering costs, and improving ROI.

Let’s use Machine Learning to take on this task!

Actions

We firstly needed to compile the necessary data from tables in the database, gathering key customer metrics that may help predict delivery club membership.

Within our historical dataset from the last campaign, we found that 69% of customers did not sign up and 31% did. This tells us that while the data isn’t perfectly balanced at 50:50, it isn’t too imbalanced either. Even so, we make sure to not rely on classification accuracy alone when assessing results - also analysing Precision, Recall, and F1-Score.

As we are predicting a binary output, we tested four classification modelling approaches, namely:

- Logistic Regression

- Decision Tree

- Random Forest

- K Nearest Neighbours (KNN)

For each model, we will import the data in the same way but will need to pre-process the data based up the requirements of each particular algorithm. We will train & test each model, look to refine each to provide optimal performance, and then measure this predictive performance based on several metrics to give a well-rounded overview of which is best.

Results

The goal for the project was to build a model that would accurately predict the customers that would sign up for the delivery club. This would allow for a much more targeted approach when running the next iteration of the campaign. A secondary goal was to understand what the drivers for this are, so the client can get closer to the customers that need or want this service, and enhance their messaging.

Based upon these, the chosen the model is the Random Forest as it was a) the most consistently performant on the test set across classication accuracy, precision, recall, and f1-score, and b) the feature importance and permutation importance allows the client an understanding of the key drivers behind delivery club signups.

Metric 1: Classification Accuracy

- KNN = 0.936

- Random Forest = 0.935

- Decision Tree = 0.929

- Logistic Regression = 0.866

Metric 2: Precision

- KNN = 1.00

- Random Forest = 0.887

- Decision Tree = 0.885

- Logistic Regression = 0.784

Metric 3: Recall

- Random Forest = 0.904

- Decision Tree = 0.885

- KNN = 0.762

- Logistic Regression = 0.69

Metric 4: F1 Score

- Random Forest = 0.895

- Decision Tree = 0.885

- KNN = 0.865

- Logistic Regression = 0.734

Growth/Next Steps

While predictive accuracy was relatively high - other modelling approaches could be tested, especially those somewhat similar to Random Forest, for example XGBoost, LightGBM to see if even more accuracy could be gained.

From a data point of view, further variables could be collected, and further feature engineering could be undertaken to ensure that we have as much useful information available for predicting customer loyalty

___

Data Overview

We will be predicting the binary signup_flag metric from the campaign_data table in the client database.

The key variables hypothesised to predict this will come from the client database, namely the transactions table, the customer_details table, and the product_areas table.

We aggregated up customer data from the 3 months prior to the last campaign.

After this data pre-processing in Python, we have a dataset for modelling that contains the following fields…

| Variable Name | Variable Type | Description |

|---|---|---|

| signup_flag | Dependent | A binary variable showing if the customer signed up for the delivery club in the last campaign |

| distance_from_store | Independent | The distance in miles from the customers home address, and the store |

| gender | Independent | The gender provided by the customer |

| credit_score | Independent | The customers most recent credit score |

| total_sales | Independent | Total spend by the customer in ABC Grocery - 3 months pre campaign |

| total_items | Independent | Total products purchased by the customer in ABC Grocery - 3 months pre campaign |

| transaction_count | Independent | Total unique transactions made by the customer in ABC Grocery - 3 months pre campaign |

| product_area_count | Independent | The number of product areas within ABC Grocery the customers has shopped into - 3 months pre campaign |

| average_basket_value | Independent | The average spend per transaction for the customer in ABC Grocery - 3 months pre campaign |

Modelling Overview

We will build a model that looks to accurately predict signup_flag, based upon the customer metrics listed above.

If that can be achieved, we can use this model to predict signup & signup probability for future campaigns. This information can be used to target those more likely to sign-up, reducing marketing costs and thus increasing ROI.

As we are predicting a binary output, we tested three classification modelling approaches, namely:

- Logistic Regression

- Decision Tree

- Random Forest

Logistic Regression

We utlise the scikit-learn library within Python to model our data using Logistic Regression. The code sections below are broken up into 5 key sections:

- Data Import

- Data Preprocessing

- Model Training

- Performance Assessment

- Optimal Threshold Analysis

Data Import

Since we saved our modelling data as a pickle file, we import it. We ensure we remove the id column, and we also ensure our data is shuffled.

We also investigate the class balance of our dependent variable - which is important when assessing classification accuracy.

# import required packages

import pandas as pd

import pickle

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import numpy as np

from sklearn.linear_model import LogisticRegression

from sklearn.utils import shuffle

from sklearn.model_selection import train_test_split, cross_val_score, KFold

from sklearn.metrics import confusion_matrix, accuracy_score, precision_score, recall_score, f1_score

from sklearn.preprocessing import OneHotEncoder

from sklearn.feature_selection import RFECV

# import modelling data

data_for_model = pickle.load(open("data/delivery_club_modelling.p", "rb"))

# drop uneccessary columns

data_for_model.drop("customer_id", axis = 1, inplace = True)

# shuffle data

data_for_model = shuffle(data_for_model, random_state = 42)

# assess class balance of dependent variable

data_for_model["signup_flag"].value_counts(normalize = True)

From the last step in the above code, we see that 69% of customers did not sign up and 31% did. This tells us that while the data isn’t perfectly balanced at 50:50, it isn’t too imbalanced either. Because of this, and as you will see, we make sure to not rely on classification accuracy alone when assessing results - also analysing Precision, Recall, and F1-Score.

Data Preprocessing

For Logistic Regression we have certain data preprocessing steps that need to be addressed, including:

- Missing values in the data

- The effect of outliers

- Encoding categorical variables to numeric form

- Multicollinearity & Feature Selection

Missing Values

The number of missing values in the data was extremely low, so instead of applying any imputation (i.e. mean, most common value) we will just remove those rows

# remove rows where values are missing

data_for_model.isna().sum()

data_for_model.dropna(how = "any", inplace = True)

Outliers

The ability for a Logistic Regression model to generalise well across all data can be hampered if there are outliers present. There is no right or wrong way to deal with outliers, but it is always something worth very careful consideration - just because a value is high or low, does not necessarily mean it should not be there!

In this code section, we use .describe() from Pandas to investigate the spread of values for each of our predictors. The results of this can be seen in the table below.

| metric | distance_from_store | credit_score | total_sales | total_items | transaction_count | product_area_count | average_basket_value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mean | 2.61 | 0.60 | 968.17 | 143.88 | 22.21 | 4.18 | 38.03 |

| std | 14.40 | 0.10 | 1073.65 | 125.34 | 11.72 | 0.92 | 24.24 |

| min | 0.00 | 0.26 | 2.09 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 2.09 |

| 25% | 0.73 | 0.53 | 383.94 | 77.00 | 16.00 | 4.00 | 21.73 |

| 50% | 1.64 | 0.59 | 691.64 | 123.00 | 23.00 | 4.00 | 31.07 |

| 75% | 2.92 | 0.67 | 1121.53 | 170.50 | 28.00 | 5.00 | 46.43 |

| max | 400.97 | 0.88 | 7372.06 | 910.00 | 75.00 | 5.00 | 141.05 |

Based on this investigation, we see some max column values for several variables to be much higher than the median value.

This is for columns distance_from_store, total_sales, and total_items

For example, the median distance_to_store is 1.64 miles, but the maximum is over 400 miles!

Because of this, we apply some outlier removal in order to facilitate generalisation across the full dataset.

We do this using the “boxplot approach” where we remove any rows where the values within those columns are outside of the interquartile range multiplied by 2.

outlier_investigation = data_for_model.describe()

outlier_columns = ["distance_from_store", "total_sales", "total_items"]

# boxplot approach

for column in outlier_columns:

lower_quartile = data_for_model[column].quantile(0.25)

upper_quartile = data_for_model[column].quantile(0.75)

iqr = upper_quartile - lower_quartile

iqr_extended = iqr * 2

min_border = lower_quartile - iqr_extended

max_border = upper_quartile + iqr_extended

outliers = data_for_model[(data_for_model[column] < min_border) | (data_for_model[column] > max_border)].index

print(f"{len(outliers)} outliers detected in column {column}")

data_for_model.drop(outliers, inplace = True)

Split Out Data For Modelling

In the next code block we do two things, we firstly split our data into an X object which contains only the predictor variables, and a y object that contains only our dependent variable.

Once we have done this, we split our data into training and test sets to ensure we can fairly validate the accuracy of the predictions on data that was not used in training. In this case, we have allocated 80% of the data for training, and the remaining 20% for validation. We make sure to add in the stratify parameter to ensure that both our training and test sets have the same proportion of customers who did, and did not, sign up for the delivery club - meaning we can be more confident in our assessment of predictive performance.

# split data into X and y objects for modelling

X = data_for_model.drop(["signup_flag"], axis = 1)

y = data_for_model["signup_flag"]

# split out training & test sets

X_train, X_test, y_train, y_test = train_test_split(X, y, test_size = 0.2, random_state = 42, stratify = y)

Categorical Predictor Variables

In our dataset, we have one categorical variable gender which has values of “M” for Male, “F” for Female, and “U” for Unknown.

The Logistic Regression algorithm can’t deal with data in this format as it can’t assign any numerical meaning to it when looking to assess the relationship between the variable and the dependent variable.

As gender doesn’t have any explicit order to it, in other words, Male isn’t higher or lower than Female and vice versa - one appropriate approach is to apply One Hot Encoding to the categorical column.

One Hot Encoding can be thought of as a way to represent categorical variables as binary vectors, in other words, a set of new columns for each categorical value with either a 1 or a 0 saying whether that value is true or not for that observation. These new columns would go into our model as input variables, and the original column is discarded.

We also drop one of the new columns using the parameter drop = “first”. We do this to avoid the dummy variable trap where our newly created encoded columns perfectly predict each other - and we run the risk of breaking the assumption that there is no multicollinearity, a requirement or at least an important consideration for some models, Linear Regression being one of them! Multicollinearity occurs when two or more input variables are highly correlated with each other, it is a scenario we attempt to avoid as in short, while it won’t neccessarily affect the predictive accuracy of our model, it can make it difficult to trust the statistics around how well the model is performing, and how much each input variable is truly having.

In the code, we also make sure to apply fit_transform to the training set, but only transform to the test set. This means the One Hot Encoding logic will learn and apply the “rules” from the training data, but only apply them to the test data. This is important in order to avoid data leakage where the test set learns information about the training data, and means we can’t fully trust model performance metrics!

For ease, after we have applied One Hot Encoding, we turn our training and test objects back into Pandas Dataframes, with the column names applied.

# list of categorical variables that need encoding

categorical_vars = ["gender"]

# instantiate OHE class

one_hot_encoder = OneHotEncoder(sparse=False, drop = "first")

# apply OHE

X_train_encoded = one_hot_encoder.fit_transform(X_train[categorical_vars])

X_test_encoded = one_hot_encoder.transform(X_test[categorical_vars])

# extract feature names for encoded columns

encoder_feature_names = one_hot_encoder.get_feature_names_out(categorical_vars)

# turn objects back to pandas dataframe

X_train_encoded = pd.DataFrame(X_train_encoded, columns = encoder_feature_names)

X_train = pd.concat([X_train.reset_index(drop=True), X_train_encoded.reset_index(drop=True)], axis = 1)

X_train.drop(categorical_vars, axis = 1, inplace = True)

X_test_encoded = pd.DataFrame(X_test_encoded, columns = encoder_feature_names)

X_test = pd.concat([X_test.reset_index(drop=True), X_test_encoded.reset_index(drop=True)], axis = 1)

X_test.drop(categorical_vars, axis = 1, inplace = True)

Feature Selection

Feature Selection is the process used to select the input variables that are most important to your Machine Learning task. It can be a very important addition or at least, consideration, in certain scenarios. The potential benefits of Feature Selection are:

- Improved Model Accuracy - eliminating noise can help true relationships stand out

- Lower Computational Cost - our model becomes faster to train, and faster to make predictions

- Explainability - understanding & explaining outputs for stakeholder & customers becomes much easier

There are many, many ways to apply Feature Selection. These range from simple methods such as a Correlation Matrix showing variable relationships, to Univariate Testing which helps us understand statistical relationships between variables, and then to even more powerful approaches like Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) which is an approach that starts with all input variables, and then iteratively removes those with the weakest relationships with the output variable.

For our task we applied a variation of Reursive Feature Elimination called Recursive Feature Elimination With Cross Validation (RFECV) where we split the data into many “chunks” and iteratively trains & validates models on each “chunk” seperately. This means that each time we assess different models with different variables included, or eliminated, the algorithm also knows how accurate each of those models was. From the suite of model scenarios that are created, the algorithm can determine which provided the best accuracy, and thus can infer the best set of input variables to use!

# instantiate RFECV & the model type to be utilised

clf = LogisticRegression(random_state = 42, max_iter = 1000)

feature_selector = RFECV(clf)

# fit RFECV onto our training & test data

fit = feature_selector.fit(X_train,y_train)

# extract & print the optimal number of features

optimal_feature_count = feature_selector.n_features_

print(f"Optimal number of features: {optimal_feature_count}")

# limit our training & test sets to only include the selected variables

X_train = X_train.loc[:, feature_selector.get_support()]

X_test = X_test.loc[:, feature_selector.get_support()]

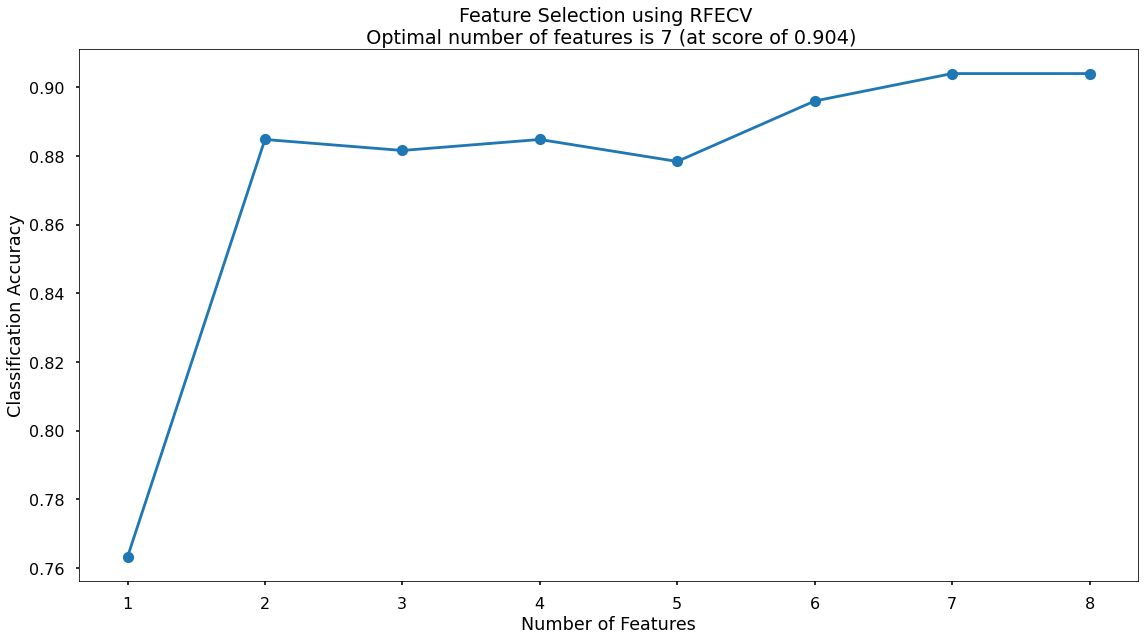

The below code then produces a plot that visualises the cross-validated classification accuracy with each potential number of features

plt.style.use('seaborn-poster')

plt.plot(range(1, len(fit.cv_results_['mean_test_score']) + 1), fit.cv_results_['mean_test_score'], marker = "o")

plt.ylabel("Classification Accuracy")

plt.xlabel("Number of Features")

plt.title(f"Feature Selection using RFECV \n Optimal number of features is {optimal_feature_count} (at score of {round(max(fit.cv_results_['mean_test_score']),4)})")

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

This creates the below plot, which shows us that the highest cross-validated classification accuracy (0.904) is when we include seven of our original input variables. The variable that has been dropped is total_sales but from the chart we can see that the difference is negligible. However, we will continue on with the selected seven!

Model Training

Instantiating and training our Logistic Regression model is done using the below code. We use the random_state parameter to ensure reproducible results, meaning any refinements can be compared to past results. We also specify max_iter = 1000 to allow the solver more attempts at finding an optimal regression line, as the default value of 100 was not enough.

# instantiate our model object

clf = LogisticRegression(random_state = 42, max_iter = 1000)

# fit our model using our training & test sets

clf.fit(X_train, y_train)

Model Performance Assessment

Predict On The Test Set

To assess how well our model is predicting on new data - we use the trained model object (here called clf) and ask it to predict the signup_flag variable for the test set.

In the code below we create one object to hold the binary 1/0 predictions, and another to hold the actual prediction probabilities for the positive class.

# predict on the test set

y_pred_class = clf.predict(X_test)

y_pred_prob = clf.predict_proba(X_test)[:,1]

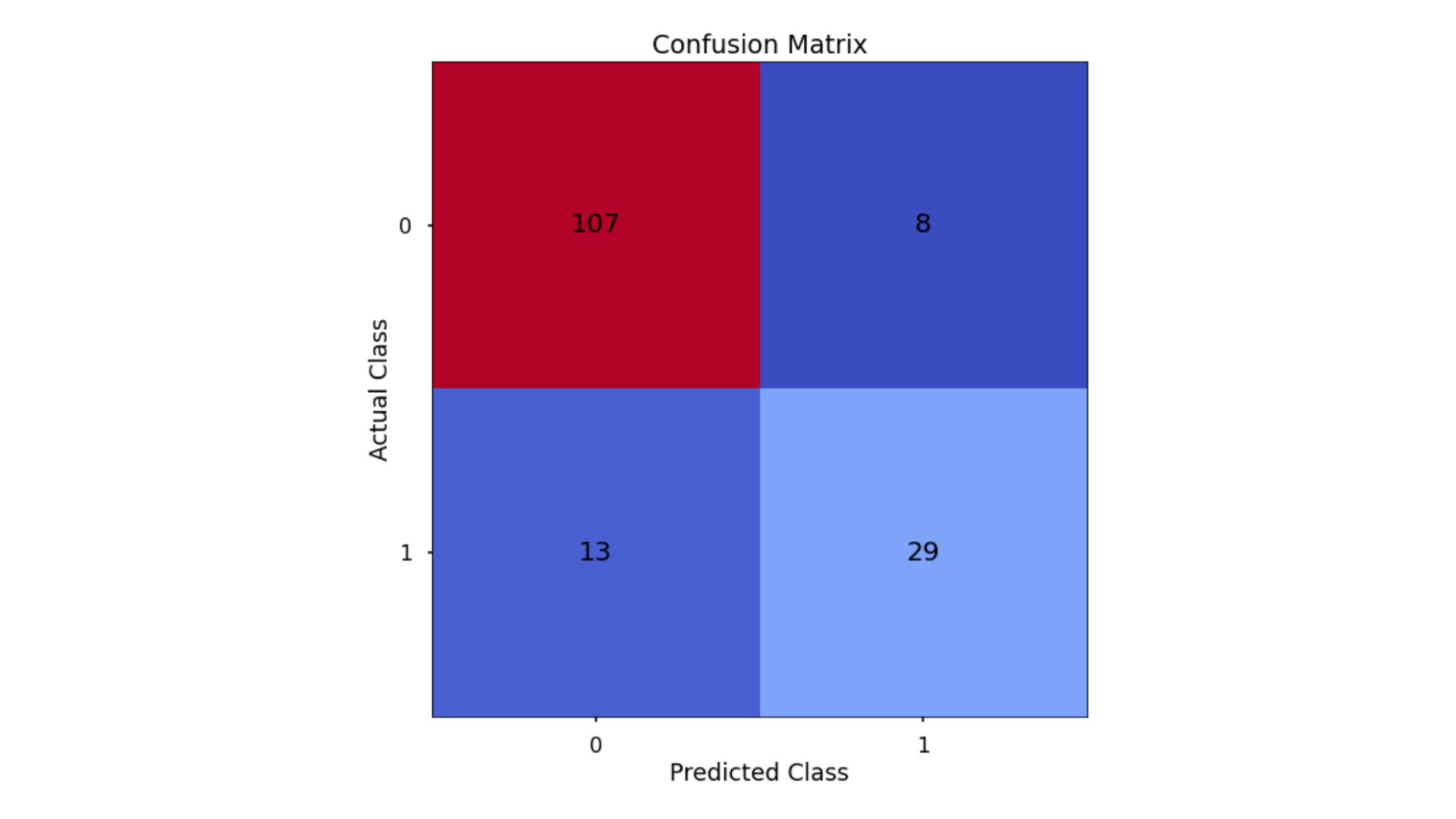

Confusion Matrix

A Confusion Matrix provides us a visual way to understand how our predictions match up against the actual values for those test set observations.

The below code creates the Confusion Matrix using the confusion_matrix functionality from within scikit-learn and then plots it using matplotlib.

# create the confusion matrix

conf_matrix = confusion_matrix(y_test, y_pred_class)

# plot the confusion matrix

plt.style.use("seaborn-poster")

plt.matshow(conf_matrix, cmap = "coolwarm")

plt.gca().xaxis.tick_bottom()

plt.title("Confusion Matrix")

plt.ylabel("Actual Class")

plt.xlabel("Predicted Class")

for (i, j), corr_value in np.ndenumerate(conf_matrix):

plt.text(j, i, corr_value, ha = "center", va = "center", fontsize = 20)

plt.show()

The aim is to have a high proportion of observations falling into the top left cell (predicted non-signup and actual non-signup) and the bottom right cell (predicted signup and actual signup).

Since the proportion of signups in our data was around 30:70 we will next analyse not only Classification Accuracy, but also Precision, Recall, and F1-Score which will help us assess how well our model has performed in reality.

Classification Performance Metrics

Classification Accuracy

Classification Accuracy is a metric that tells us of all predicted observations, what proportion did we correctly classify. This is very intuitive, but when dealing with imbalanced classes, can be misleading.

An example of this could be a rare disease. A model with a 98% Classification Accuracy on might appear like a fantastic result, but if our data contained 98% of patients without the disease, and 2% with the disease - then a 98% Classification Accuracy could be obtained simply by predicting that no one has the disease - which wouldn’t be a great model in the real world. Luckily, there are other metrics which can help us!

In this example of the rare disease, we could define Classification Accuracy as of all predicted patients, what proportion did we correctly classify as either having the disease, or not having the disease

Precision & Recall

Precision is a metric that tells us of all observations that were predicted as positive, how many actually were positive

Keeping with the rare disease example, Precision would tell us of all patients we predicted to have the disease, how many actually did

Recall is a metric that tells us of all positive observations, how many did we predict as positive

Again, referring to the rare disease example, Recall would tell us of all patients who actually had the disease, how many did we correctly predict

The tricky thing about Precision & Recall is that it is impossible to optimise both - it’s a zero-sum game. If you try to increase Precision, Recall decreases, and vice versa. Sometimes however it will make more sense to try and elevate one of them, in spite of the other. In the case of our rare-disease prediction like we’ve used in our example, perhaps it would be more important to optimise for Recall as we want to classify as many positive cases as possible. In saying this however, we don’t want to just classify every patient as having the disease, as that isn’t a great outcome either!

So - there is one more metric we will discuss & calculate, which is actually a combination of both…

F1 Score

F1-Score is a metric that essentially “combines” both Precision & Recall. Technically speaking, it is the harmonic mean of these two metrics. A good, or high, F1-Score comes when there is a balance between Precision & Recall, rather than a disparity between them.

Overall, optimising your model for F1-Score means that you’ll get a model that is working well for both positive & negative classifications rather than skewed towards one or the other. To return to the rare disease predictions, a high F1-Score would mean we’ve got a good balance between successfully predicting the disease when it’s present, and not predicting cases where it’s not present.

Using all of these metrics in combination gives a really good overview of the performance of a classification model, and gives us an understanding of the different scenarios & considerations!

In the code below, we utilise in-built functionality from scikit-learn to calculate these four metrics.

# classification accuracy

accuracy_score(y_test, y_pred_class)

# precision

precision_score(y_test, y_pred_class)

# recall

recall_score(y_test, y_pred_class)

# f1-score

f1_score(y_test, y_pred_class)

Running this code gives us:

- Classification Accuracy = 0.866 meaning we correctly predicted the class of 86.6% of test set observations

- Precision = 0.784 meaning that for our predicted delivery club signups, we were correct 78.4% of the time

- Recall = 0.69 meaning that of all actual delivery club signups, we predicted correctly 69% of the time

- F1-Score = 0.734

Since our data is somewhat imbalanced, looking at these metrics rather than just Classification Accuracy on it’s own - is a good idea, and gives us a much better understanding of what our predictions mean! We will use these same metrics when applying other models for this task, and can compare how they stack up.

Finding The Optimal Classification Threshold

By default, most pre-built classification models & algorithms will just use a 50% probability to discern between a positive class prediction (delivery club signup) and a negative class prediction (delivery club non-signup).

Just because 50% is the default threshold does not mean it is the best one for our task.

Here, we will test many potential classification thresholds, and plot the Precision, Recall & F1-Score, and find an optimal solution!

# set up the list of thresholds to loop through

thresholds = np.arange(0, 1, 0.01)

# create empty lists to append the results to

precision_scores = []

recall_scores = []

f1_scores = []

# loop through each threshold - fit the model - append the results

for threshold in thresholds:

pred_class = (y_pred_prob >= threshold) * 1

precision = precision_score(y_test, pred_class, zero_division = 0)

precision_scores.append(precision)

recall = recall_score(y_test, pred_class)

recall_scores.append(recall)

f1 = f1_score(y_test, pred_class)

f1_scores.append(f1)

# extract the optimal f1-score (and it's index)

max_f1 = max(f1_scores)

max_f1_idx = f1_scores.index(max_f1)

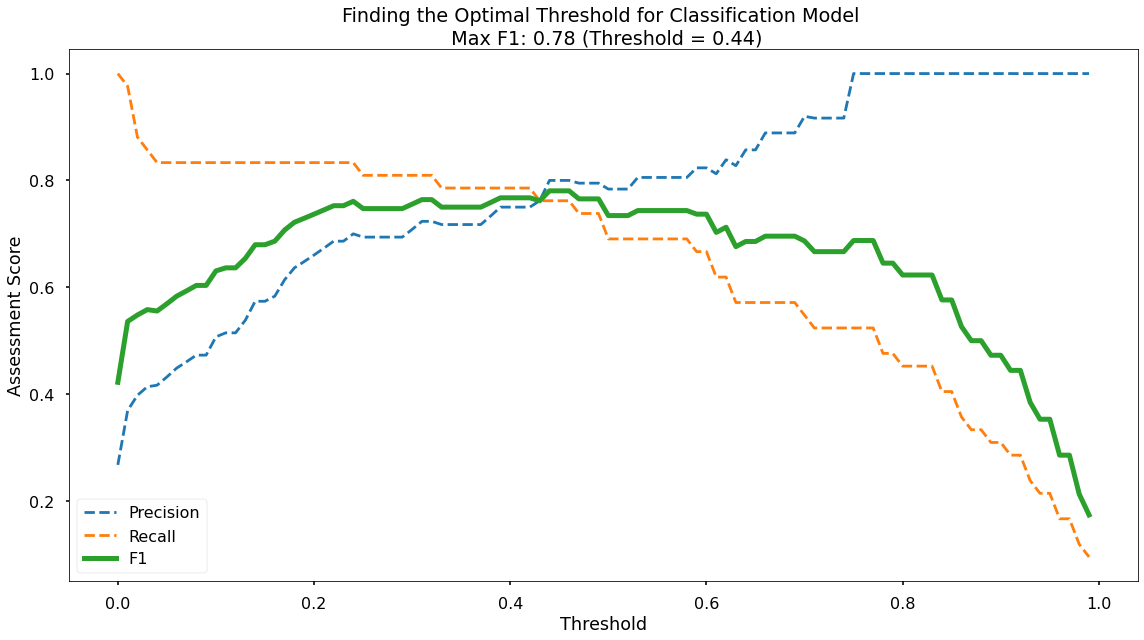

Now we have run this, we can use the below code to plot the results!

# plot the results

plt.style.use("seaborn-poster")

plt.plot(thresholds, precision_scores, label = "Precision", linestyle = "--")

plt.plot(thresholds, recall_scores, label = "Recall", linestyle = "--")

plt.plot(thresholds, f1_scores, label = "F1", linewidth = 5)

plt.title(f"Finding the Optimal Threshold for Classification Model \n Max F1: {round(max_f1,2)} (Threshold = {round(thresholds[max_f1_idx],2)})")

plt.xlabel("Threshold")

plt.ylabel("Assessment Score")

plt.legend(loc = "lower left")

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

Along the x-axis of the above plot we have the different classification thresholds that were testing. Along the y-axis we have the performance score for each of our three metrics. As per the legend, we have Precision as a blue dotted line, Recall as an orange dotted line, and F1-Score as a thick green line. You can see the interesting “zero-sum” relationship between Precision & Recall and you can see that the point where Precision & Recall meet is where F1-Score is maximised.

As you can see at the top of the plot, the optimal F1-Score for this model 0.78 and this is obtained at a classification threshold of 0.44. This is higher than the F1-Score of 0.734 that we achieved at the default classification threshold of 0.50!

Decision Tree

We will again utlise the scikit-learn library within Python to model our data using a Decision Tree. The code sections below are broken up into 6 key sections:

- Data Import

- Data Preprocessing

- Model Training

- Performance Assessment

- Tree Visualisation

- Decision Tree Regularisation

Data Import

Since we saved our modelling data as a pickle file, we import it. We ensure we remove the id column, and we also ensure our data is shuffled.

Just like we did for Logistic Regression - our code also investigates the class balance of our dependent variable.

# import required packages

import pandas as pd

import pickle

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import numpy as np

from sklearn.tree import DecisionTreeClassifier, plot_tree

from sklearn.utils import shuffle

from sklearn.model_selection import train_test_split, cross_val_score, KFold

from sklearn.metrics import confusion_matrix, accuracy_score, precision_score, recall_score, f1_score

from sklearn.preprocessing import OneHotEncoder

# import modelling data

data_for_model = pickle.load(open("data/delivery_club_modelling.p", "rb"))

# drop uneccessary columns

data_for_model.drop("customer_id", axis = 1, inplace = True)

# shuffle data

data_for_model = shuffle(data_for_model, random_state = 42)

# assess class balance of dependent variable

data_for_model["signup_flag"].value_counts(normalize = True)

Data Preprocessing

While Logistic Regression is susceptible to the effects of outliers, and highly correlated input variables - Decision Trees are not, so the required preprocessing here is lighter. We still however will put in place logic for:

- Missing values in the data

- Encoding categorical variables to numeric form

Missing Values

The number of missing values in the data was extremely low, so instead of applying any imputation (i.e. mean, most common value) we will just remove those rows

# remove rows where values are missing

data_for_model.isna().sum()

data_for_model.dropna(how = "any", inplace = True)

Split Out Data For Modelling

In exactly the same way we did for Logistic Regression, in the next code block we do two things, we firstly split our data into an X object which contains only the predictor variables, and a y object that contains only our dependent variable.

Once we have done this, we split our data into training and test sets to ensure we can fairly validate the accuracy of the predictions on data that was not used in training. In this case, we have allocated 80% of the data for training, and the remaining 20% for validation. Again, we make sure to add in the stratify parameter to ensure that both our training and test sets have the same proportion of customers who did, and did not, sign up for the delivery club - meaning we can be more confident in our assessment of predictive performance.

# split data into X and y objects for modelling

X = data_for_model.drop(["signup_flag"], axis = 1)

y = data_for_model["signup_flag"]

# split out training & test sets

X_train, X_test, y_train, y_test = train_test_split(X, y, test_size = 0.2, random_state = 42, stratify = y)

Categorical Predictor Variables

In our dataset, we have one categorical variable gender which has values of “M” for Male, “F” for Female, and “U” for Unknown.

Just like the Logisitc Regression algorithm, the Decision Tree cannot deal with data in this format as it can’t assign any numerical meaning to it when looking to assess the relationship between the variable and the dependent variable.

As gender doesn’t have any explicit order to it, in other words, Male isn’t higher or lower than Female and vice versa - we would again apply One Hot Encoding to the categorical column.

# list of categorical variables that need encoding

categorical_vars = ["gender"]

# instantiate OHE class

one_hot_encoder = OneHotEncoder(sparse=False, drop = "first")

# apply OHE

X_train_encoded = one_hot_encoder.fit_transform(X_train[categorical_vars])

X_test_encoded = one_hot_encoder.transform(X_test[categorical_vars])

# extract feature names for encoded columns

encoder_feature_names = one_hot_encoder.get_feature_names_out(categorical_vars)

# turn objects back to pandas dataframe

X_train_encoded = pd.DataFrame(X_train_encoded, columns = encoder_feature_names)

X_train = pd.concat([X_train.reset_index(drop=True), X_train_encoded.reset_index(drop=True)], axis = 1)

X_train.drop(categorical_vars, axis = 1, inplace = True)

X_test_encoded = pd.DataFrame(X_test_encoded, columns = encoder_feature_names)

X_test = pd.concat([X_test.reset_index(drop=True), X_test_encoded.reset_index(drop=True)], axis = 1)

X_test.drop(categorical_vars, axis = 1, inplace = True)

Model Training

Instantiating and training our Decision Tree model is done using the below code. We use the random_state parameter to ensure we get reproducible results, and this helps us understand any improvements in performance with changes to model hyperparameters.

# instantiate our model object

clf = DecisionTreeClassifier(random_state = 42, max_depth = 5)

# fit our model using our training & test sets

clf.fit(X_train, y_train)

Model Performance Assessment

Predict On The Test Set

Just like we did with Logistic Regression, to assess how well our model is predicting on new data - we use the trained model object (here called clf) and ask it to predict the signup_flag variable for the test set.

In the code below we create one object to hold the binary 1/0 predictions, and another to hold the actual prediction probabilities for the positive class.

# predict on the test set

y_pred_class = clf.predict(X_test)

y_pred_prob = clf.predict_proba(X_test)[:,1]

Confusion Matrix

As we discussed in the above section applying Logistic Regression - a Confusion Matrix provides us a visual way to understand how our predictions match up against the actual values for those test set observations.

The below code creates the Confusion Matrix using the confusion_matrix functionality from within scikit-learn and then plots it using matplotlib.

# create the confusion matrix

conf_matrix = confusion_matrix(y_test, y_pred_class)

# plot the confusion matrix

plt.style.use("seaborn-poster")

plt.matshow(conf_matrix, cmap = "coolwarm")

plt.gca().xaxis.tick_bottom()

plt.title("Confusion Matrix")

plt.ylabel("Actual Class")

plt.xlabel("Predicted Class")

for (i, j), corr_value in np.ndenumerate(conf_matrix):

plt.text(j, i, corr_value, ha = "center", va = "center", fontsize = 20)

plt.show()

The aim is to have a high proportion of observations falling into the top left cell (predicted non-signup and actual non-signup) and the bottom right cell (predicted signup and actual signup).

Since the proportion of signups in our data was around 30:70 we will again analyse not only Classification Accuracy, but also Precision, Recall, and F1-Score as they will help us assess how well our model has performed from different points of view.

Classification Performance Metrics

Accuracy, Precision, Recall, F1-Score

For details on these performance metrics, please see the above section on Logistic Regression. Using all four of these metrics in combination gives a really good overview of the performance of a classification model, and gives us an understanding of the different scenarios & considerations!

In the code below, we utilise in-built functionality from scikit-learn to calculate these four metrics.

# classification accuracy

accuracy_score(y_test, y_pred_class)

# precision

precision_score(y_test, y_pred_class)

# recall

recall_score(y_test, y_pred_class)

# f1-score

f1_score(y_test, y_pred_class)

Running this code gives us:

- Classification Accuracy = 0.929 meaning we correctly predicted the class of 92.9% of test set observations

- Precision = 0.885 meaning that for our predicted delivery club signups, we were correct 88.5% of the time

- Recall = 0.885 meaning that of all actual delivery club signups, we predicted correctly 88.5% of the time

- F1-Score = 0.885

These are all higher than what we saw when applying Logistic Regression, even after we had optimised the classification threshold!

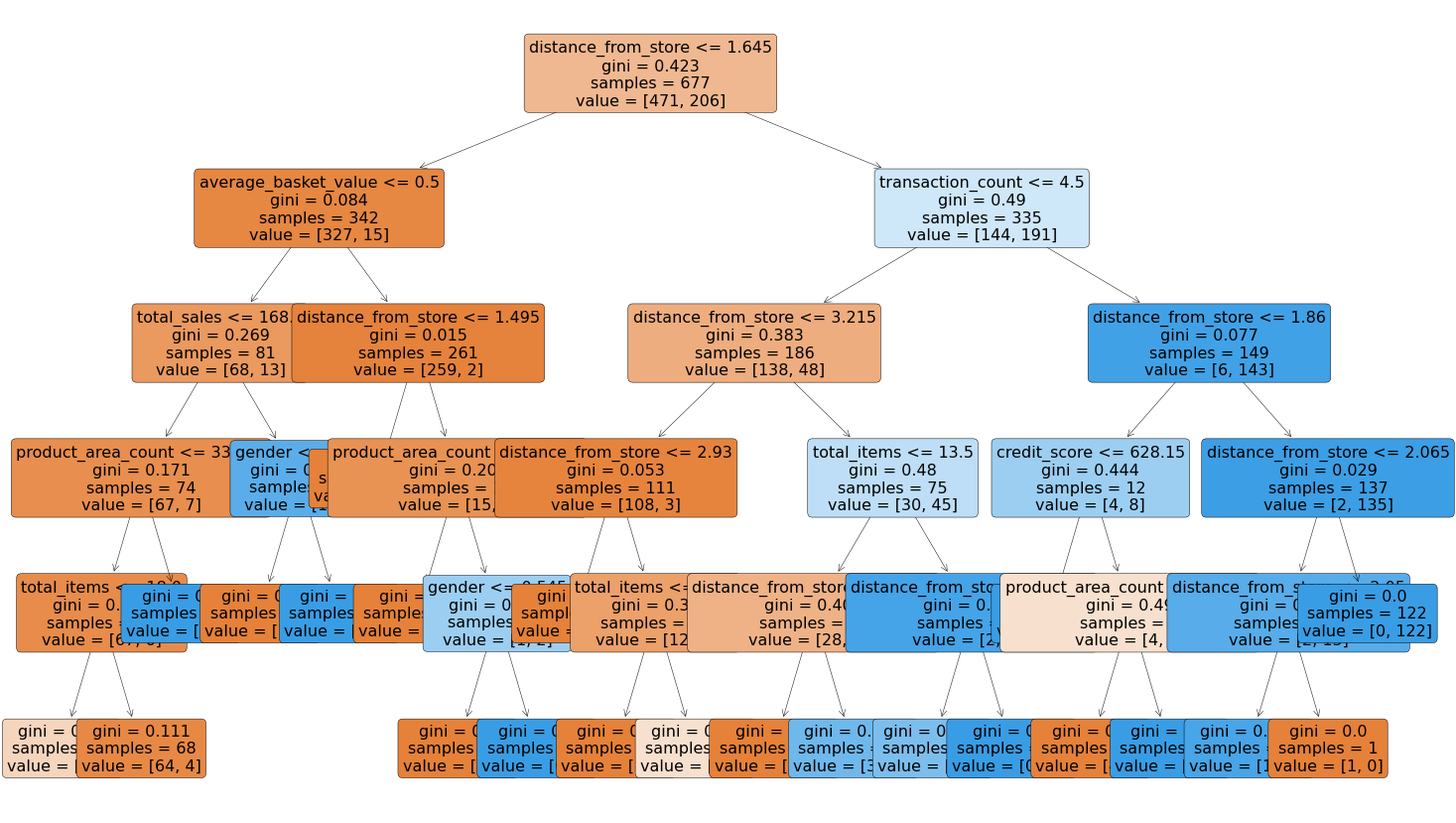

Visualise Our Decision Tree

To see the decisions that have been made in the tree, we can use the plot_tree functionality that we imported from scikit-learn. To do this, we use the below code:

# plot the nodes of the decision tree

plt.figure(figsize=(25,15))

tree = plot_tree(clf,

feature_names = X.columns,

filled = True,

rounded = True,

fontsize = 16)

That code gives us the below plot:

This is a very powerful visual, and one that can be shown to stakeholders in the business to ensure they understand exactly what is driving the predictions.

One interesting thing to note is that the very first split appears to be using the variable distance from store so it would seem that this is a very important variable when it comes to predicting signups to the delivery club!

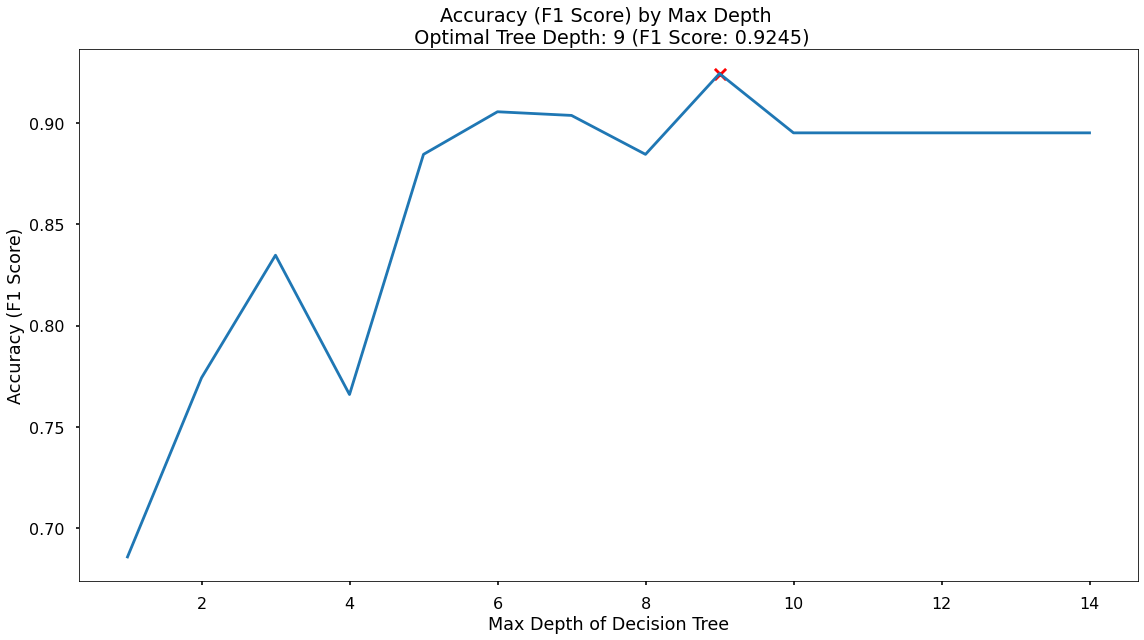

Decision Tree Regularisation

Decision Tree’s can be prone to over-fitting, in other words, without any limits on their splitting, they will end up learning the training data perfectly. We would much prefer our model to have a more generalised set of rules, as this will be more robust & reliable when making predictions on new data.

One effective method of avoiding this over-fitting, is to apply a max depth to the Decision Tree, meaning we only allow it to split the data a certain number of times before it is required to stop.

We initially trained our model with a placeholder depth of 5, but unfortunately, we don’t necessarily know the optimal number for this. Below we will loop over a variety of values and assess which gives us the best predictive performance!

# finding the best max_depth

# set up range for search, and empty list to append accuracy scores to

max_depth_list = list(range(1,15))

accuracy_scores = []

# loop through each possible depth, train and validate model, append test set f1-score

for depth in max_depth_list:

clf = DecisionTreeClassifier(max_depth = depth, random_state = 42)

clf.fit(X_train,y_train)

y_pred = clf.predict(X_test)

accuracy = f1_score(y_test,y_pred)

accuracy_scores.append(accuracy)

# store max accuracy, and optimal depth

max_accuracy = max(accuracy_scores)

max_accuracy_idx = accuracy_scores.index(max_accuracy)

optimal_depth = max_depth_list[max_accuracy_idx]

# plot accuracy by max depth

plt.plot(max_depth_list,accuracy_scores)

plt.scatter(optimal_depth, max_accuracy, marker = "x", color = "red")

plt.title(f"Accuracy (F1 Score) by Max Depth \n Optimal Tree Depth: {optimal_depth} (F1 Score: {round(max_accuracy,4)})")

plt.xlabel("Max Depth of Decision Tree")

plt.ylabel("Accuracy (F1 Score)")

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

That code gives us the below plot - which visualises the results!

In the plot we can see that the maximum F1-Score on the test set is found when applying a max_depth value of 9 which takes our F1-Score up to 0.925

Random Forest

We will again utlise the scikit-learn library within Python to model our data using a Random Forest. The code sections below are broken up into 4 key sections:

- Data Import

- Data Preprocessing

- Model Training

- Performance Assessment

Data Import

Again, since we saved our modelling data as a pickle file, we import it. We ensure we remove the id column, and we also ensure our data is shuffled.

As this is the exact same process we ran for both Logistic Regression & the Decision Tree - our code also investigates the class balance of our dependent variable

# import required packages

import pandas as pd

import pickle

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import numpy as np

from sklearn.ensemble import RandomForestClassifier

from sklearn.utils import shuffle

from sklearn.model_selection import train_test_split, cross_val_score, KFold

from sklearn.metrics import confusion_matrix, accuracy_score, precision_score, recall_score, f1_score

from sklearn.preprocessing import OneHotEncoder

from sklearn.inspection import permutation_importance

# import modelling data

data_for_model = pickle.load(open("data/delivery_club_modelling.p", "rb"))

# drop uneccessary columns

data_for_model.drop("customer_id", axis = 1, inplace = True)

# shuffle data

data_for_model = shuffle(data_for_model, random_state = 42)

Data Preprocessing

While Linear Regression is susceptible to the effects of outliers, and highly correlated input variables - Random Forests, just like Decision Trees, are not, so the required preprocessing here is lighter. We still however will put in place logic for:

- Missing values in the data

- Encoding categorical variables to numeric form

Missing Values

The number of missing values in the data was extremely low, so instead of applying any imputation (i.e. mean, most common value) we will just remove those rows. Again, this is exactly the same process we ran for Logistic Regression & the Decision Tree.

# remove rows where values are missing

data_for_model.isna().sum()

data_for_model.dropna(how = "any", inplace = True)

Split Out Data For Modelling

In exactly the same way we did for both Logistic Regression & our Decision Tree, in the next code block we do two things, we firstly split our data into an X object which contains only the predictor variables, and a y object that contains only our dependent variable.

Once we have done this, we split our data into training and test sets to ensure we can fairly validate the accuracy of the predictions on data that was not used in training. In this case, we have allocated 80% of the data for training, and the remaining 20% for validation. Again, we make sure to add in the stratify parameter to ensure that both our training and test sets have the same proportion of customers who did, and did not, sign up for the delivery club - meaning we can be more confident in our assessment of predictive performance.

# split data into X and y objects for modelling

X = data_for_model.drop(["signup_flag"], axis = 1)

y = data_for_model["signup_flag"]

# split out training & test sets

X_train, X_test, y_train, y_test = train_test_split(X, y, test_size = 0.2, random_state = 42, stratify = y)

Categorical Predictor Variables

In our dataset, we have one categorical variable gender which has values of “M” for Male, “F” for Female, and “U” for Unknown.

Just like the Logistic Regression algorithm, Random Forests cannot deal with data in this format as it can’t assign any numerical meaning to it when looking to assess the relationship between the variable and the dependent variable.

As gender doesn’t have any explicit order to it, in other words, Male isn’t higher or lower than Female and vice versa - we would again apply One Hot Encoding to the categorical column.

# list of categorical variables that need encoding

categorical_vars = ["gender"]

# instantiate OHE class

one_hot_encoder = OneHotEncoder(sparse=False, drop = "first")

# apply OHE

X_train_encoded = one_hot_encoder.fit_transform(X_train[categorical_vars])

X_test_encoded = one_hot_encoder.transform(X_test[categorical_vars])

# extract feature names for encoded columns

encoder_feature_names = one_hot_encoder.get_feature_names_out(categorical_vars)

# turn objects back to pandas dataframe

X_train_encoded = pd.DataFrame(X_train_encoded, columns = encoder_feature_names)

X_train = pd.concat([X_train.reset_index(drop=True), X_train_encoded.reset_index(drop=True)], axis = 1)

X_train.drop(categorical_vars, axis = 1, inplace = True)

X_test_encoded = pd.DataFrame(X_test_encoded, columns = encoder_feature_names)

X_test = pd.concat([X_test.reset_index(drop=True), X_test_encoded.reset_index(drop=True)], axis = 1)

X_test.drop(categorical_vars, axis = 1, inplace = True)

Model Training

Instantiating and training our Random Forest model is done using the below code. We use the random_state parameter to ensure we get reproducible results, and this helps us understand any improvements in performance with changes to model hyperparameters.

We also look to build more Decision Trees in the Random Forest (500) than would be done using the default value of 100.

Lastly, since the default scikit-learn implementation of Random Forests does not limit the number of randomly selected variables offered up for splitting at each split point in each Decision Tree - we put this in place using the max_features parameter. This can always be refined later through testing, or through an approach such as gridsearch.

# instantiate our model object

clf = RandomForestClassifier(random_state = 42, n_estimators = 500, max_features = 5)

# fit our model using our training & test sets

clf.fit(X_train, y_train)

Model Performance Assessment

Predict On The Test Set

Just like we did with Logistic Regression & our Decision Tree, to assess how well our model is predicting on new data - we use the trained model object (here called clf) and ask it to predict the signup_flag variable for the test set.

In the code below we create one object to hold the binary 1/0 predictions, and another to hold the actual prediction probabilities for the positive class.

# predict on the test set

y_pred_class = clf.predict(X_test)

y_pred_prob = clf.predict_proba(X_test)[:,1]

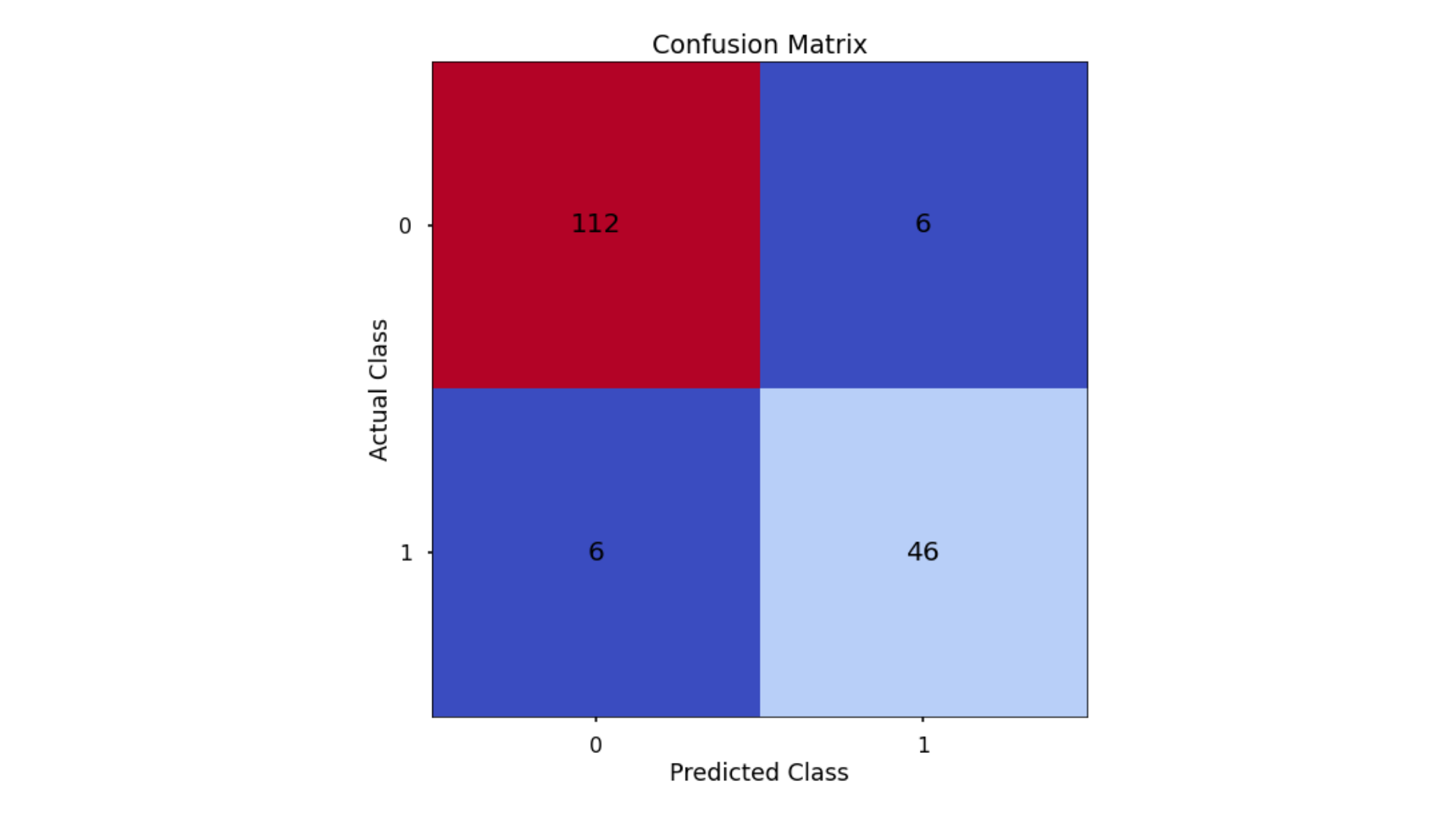

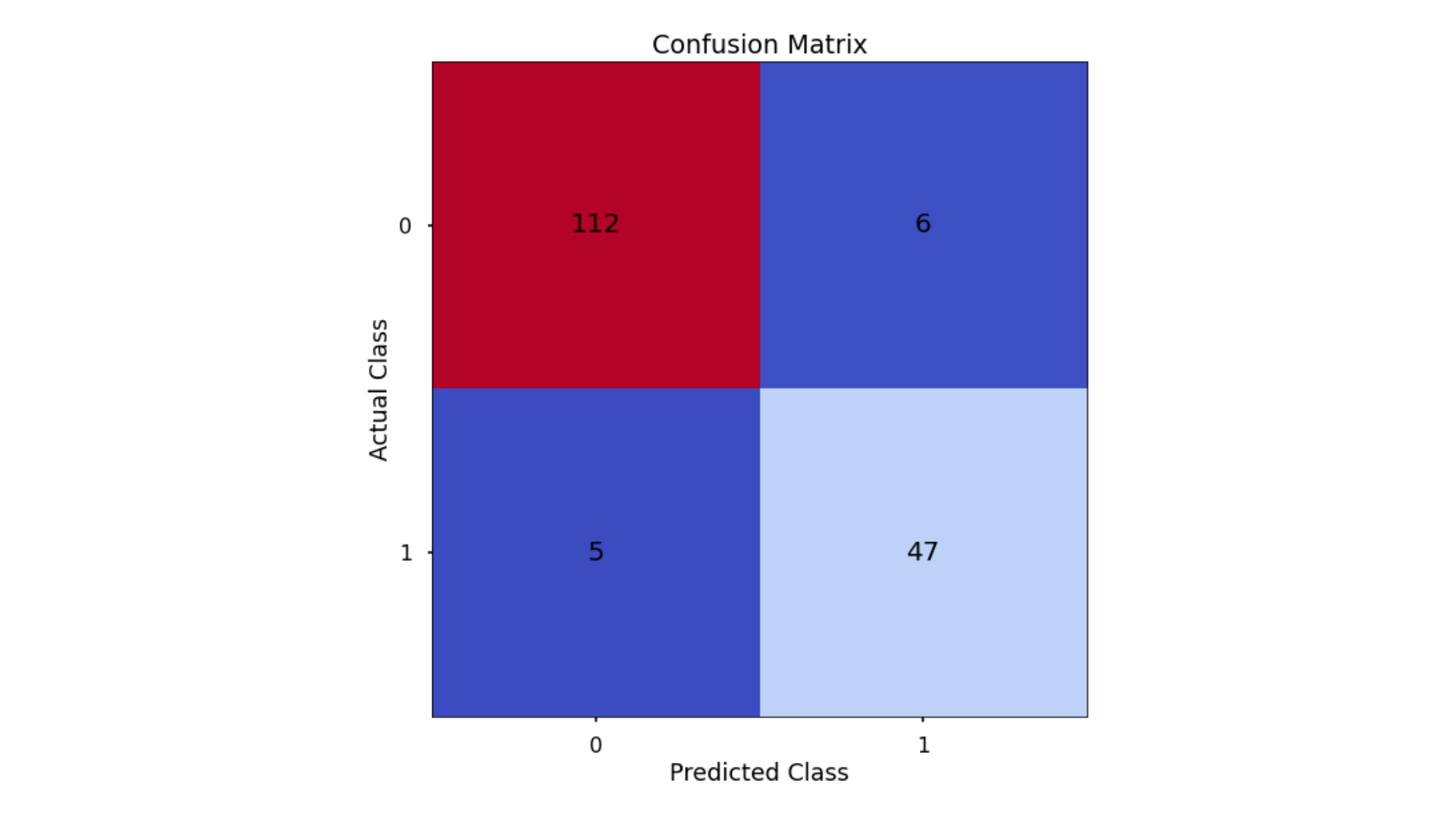

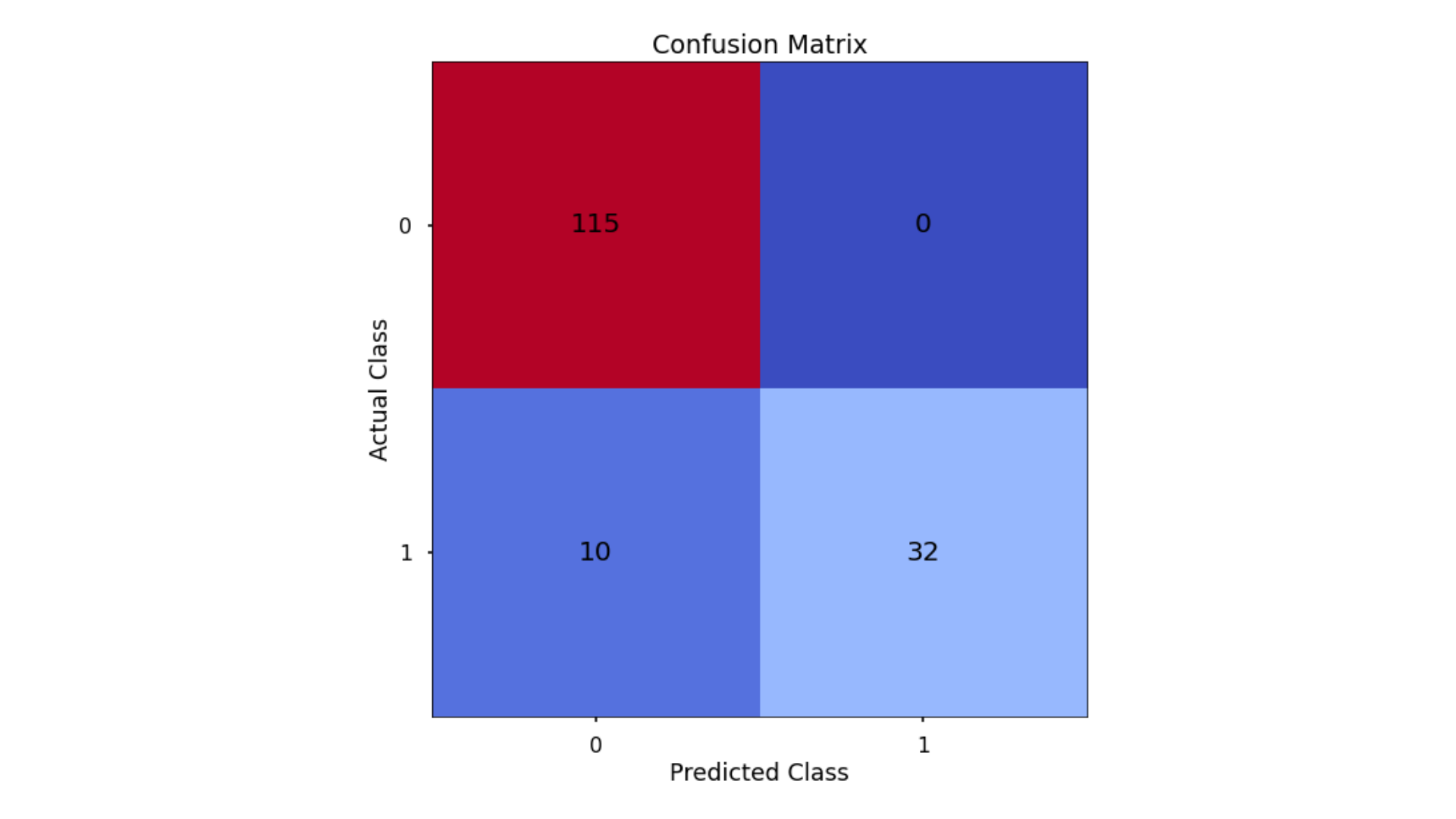

Confusion Matrix

As we discussed in the above sections - a Confusion Matrix provides us a visual way to understand how our predictions match up against the actual values for those test set observations.

The below code creates the Confusion Matrix using the confusion_matrix functionality from within scikit-learn and then plots it using matplotlib.

# create the confusion matrix

conf_matrix = confusion_matrix(y_test, y_pred_class)

# plot the confusion matrix

plt.style.use("seaborn-poster")

plt.matshow(conf_matrix, cmap = "coolwarm")

plt.gca().xaxis.tick_bottom()

plt.title("Confusion Matrix")

plt.ylabel("Actual Class")

plt.xlabel("Predicted Class")

for (i, j), corr_value in np.ndenumerate(conf_matrix):

plt.text(j, i, corr_value, ha = "center", va = "center", fontsize = 20)

plt.show()

The aim is to have a high proportion of observations falling into the top left cell (predicted non-signup and actual non-signup) and the bottom right cell (predicted signup and actual signup).

Since the proportion of signups in our data was around 30:70 we will again analyse not only Classification Accuracy, but also Precision, Recall, and F1-Score as they will help us assess how well our model has performed from different points of view.

Classification Performance Metrics

Accuracy, Precision, Recall, F1-Score

For details on these performance metrics, please see the above section on Logistic Regression. Using all four of these metrics in combination gives a really good overview of the performance of a classification model, and gives us an understanding of the different scenarios & considerations!

In the code below, we utilise in-built functionality from scikit-learn to calculate these four metrics.

# classification accuracy

accuracy_score(y_test, y_pred_class)

# precision

precision_score(y_test, y_pred_class)

# recall

recall_score(y_test, y_pred_class)

# f1-score

f1_score(y_test, y_pred_class)

Running this code gives us:

- Classification Accuracy = 0.935 meaning we correctly predicted the class of 93.5% of test set observations

- Precision = 0.887 meaning that for our predicted delivery club signups, we were correct 88.7% of the time

- Recall = 0.904 meaning that of all actual delivery club signups, we predicted correctly 90.4% of the time

- F1-Score = 0.895

These are all higher than what we saw when applying Logistic Regression, and marginally higher than what we got from our Decision Tree. If we are after out and out accuracy then this would be the best model to choose. If we were happier with a simpler, easier explain model, but that had almost the same performance - then we may choose the Decision Tree instead!

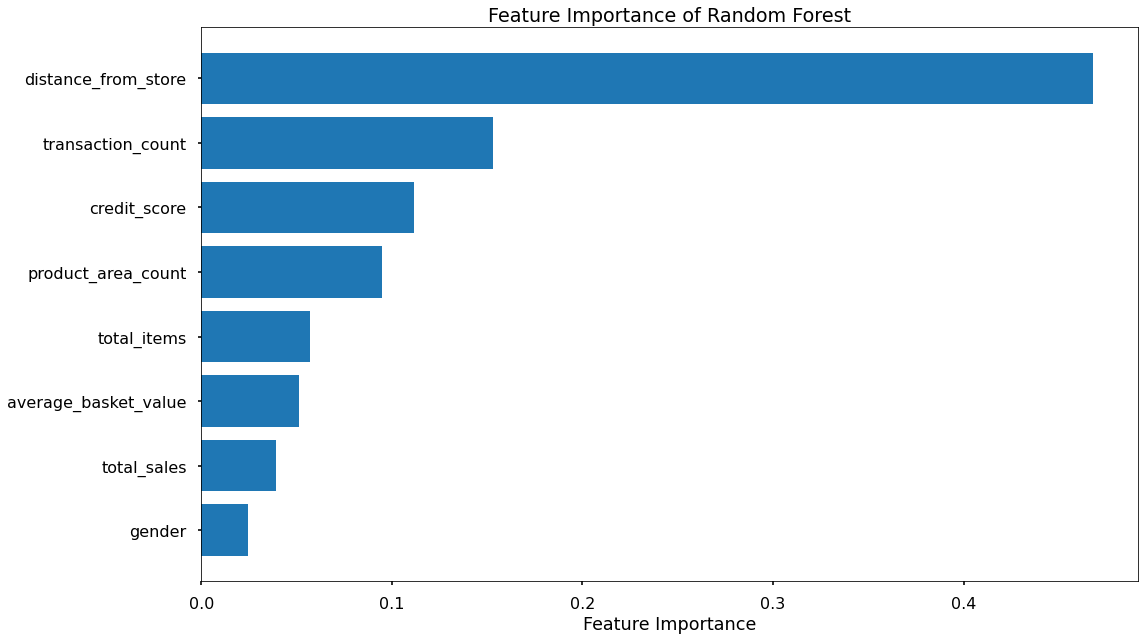

Feature Importance

Random Forests are an ensemble model, made up of many, many Decision Trees, each of which is different due to the randomness of the data being provided, and the random selection of input variables available at each potential split point.

Because of this, we end up with a powerful and robust model, but because of the random or different nature of all these Decision trees - the model gives us a unique insight into how important each of our input variables are to the overall model.

As we’re using random samples of data, and input variables for each Decision Tree - there are many scenarios where certain input variables are being held back and this enables us a way to compare how accurate the models predictions are if that variable is or isn’t present.

So, at a high level, in a Random Forest we can measure importance by asking How much would accuracy decrease if a specific input variable was removed or randomised?

If this decrease in performance, or accuracy, is large, then we’d deem that input variable to be quite important, and if we see only a small decrease in accuracy, then we’d conclude that the variable is of less importance.

At a high level, there are two common ways to tackle this. The first, often just called Feature Importance is where we find all nodes in the Decision Trees of the forest where a particular input variable is used to split the data and assess what the gini impurity score (for a Classification problem) was before the split was made, and compare this to the gini impurity score after the split was made. We can take the average of these improvements across all Decision Trees in the Random Forest to get a score that tells us how much better we’re making the model by using that input variable.

If we do this for each of our input variables, we can compare these scores and understand which is adding the most value to the predictive power of the model!

The other approach, often called Permutation Importance cleverly uses some data that has gone unused at when random samples are selected for each Decision Tree (this stage is called “bootstrap sampling” or “bootstrapping”)

These observations that were not randomly selected for each Decision Tree are known as Out of Bag observations and these can be used for testing the accuracy of each particular Decision Tree.

For each Decision Tree, all of the Out of Bag observations are gathered and then passed through. Once all of these observations have been run through the Decision Tree, we obtain a classification accuracy score for these predictions.

In order to understand the importance, we randomise the values within one of the input variables - a process that essentially destroys any relationship that might exist between that input variable and the output variable - and run that updated data through the Decision Tree again, obtaining a second accuracy score. The difference between the original accuracy and the new accuracy gives us a view on how important that particular variable is for predicting the output.

Permutation Importance is often preferred over Feature Importance which can at times inflate the importance of numerical features. Both are useful, and in most cases will give fairly similar results.

Let’s put them both in place, and plot the results…

# calculate feature importance

feature_importance = pd.DataFrame(clf.feature_importances_)

feature_names = pd.DataFrame(X.columns)

feature_importance_summary = pd.concat([feature_names,feature_importance], axis = 1)

feature_importance_summary.columns = ["input_variable","feature_importance"]

feature_importance_summary.sort_values(by = "feature_importance", inplace = True)

# plot feature importance

plt.barh(feature_importance_summary["input_variable"],feature_importance_summary["feature_importance"])

plt.title("Feature Importance of Random Forest")

plt.xlabel("Feature Importance")

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

# calculate permutation importance

result = permutation_importance(clf, X_test, y_test, n_repeats = 10, random_state = 42)

permutation_importance = pd.DataFrame(result["importances_mean"])

feature_names = pd.DataFrame(X.columns)

permutation_importance_summary = pd.concat([feature_names,permutation_importance], axis = 1)

permutation_importance_summary.columns = ["input_variable","permutation_importance"]

permutation_importance_summary.sort_values(by = "permutation_importance", inplace = True)

# plot permutation importance

plt.barh(permutation_importance_summary["input_variable"],permutation_importance_summary["permutation_importance"])

plt.title("Permutation Importance of Random Forest")

plt.xlabel("Permutation Importance")

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

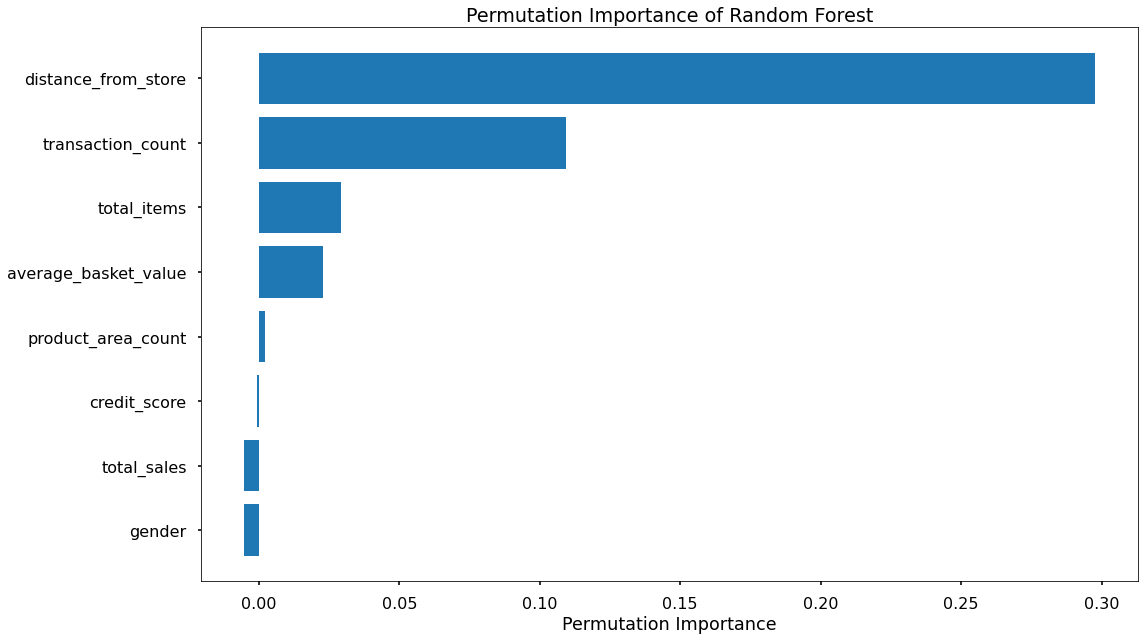

That code gives us the below plots - the first being for Feature Importance and the second for Permutation Importance!

The overall story from both approaches is very similar, in that by far, the most important or impactful input variables are distance_from_store and transaction_count

Surprisingly, average_basket_size was not as important as hypothesised.

There are slight differences in the order or “importance” for the remaining variables but overall they have provided similar findings.

K Nearest Neighbours

We utlise the scikit-learn library within Python to model our data using KNN. The code sections below are broken up into 5 key sections:

- Data Import

- Data Preprocessing

- Model Training

- Performance Assessment

- Optimal Value For K

Data Import

Again, since we saved our modelling data as a pickle file, we import it. We ensure we remove the id column, and we also ensure our data is shuffled.

As with the other approaches, we also investigate the class balance of our dependent variable - which is important when assessing classification accuracy.

# import required packages

import pandas as pd

import pickle

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import numpy as np

from sklearn.neighbors import KNeighborsClassifier

from sklearn.utils import shuffle

from sklearn.model_selection import train_test_split, cross_val_score, KFold

from sklearn.metrics import confusion_matrix, accuracy_score, precision_score, recall_score, f1_score

from sklearn.preprocessing import OneHotEncoder, MinMaxScaler

from sklearn.feature_selection import RFECV

# import modelling data

data_for_model = pickle.load(open("data/delivery_club_modelling.p", "rb"))

# drop uneccessary columns

data_for_model.drop("customer_id", axis = 1, inplace = True)

# shuffle data

data_for_model = shuffle(data_for_model, random_state = 42)

# assess class balance of dependent variable

data_for_model["signup_flag"].value_counts(normalize = True)

From the last step in the above code, we see that 69% of customers did not sign up and 31% did. This tells us that while the data isn’t perfectly balanced at 50:50, it isn’t too imbalanced either. Because of this, and as you will see, we make sure to not rely on classification accuracy alone when assessing results - also analysing Precision, Recall, and F1-Score.

Data Preprocessing

For KNN, as it is a distance based algorithm, we have certain data preprocessing steps that need to be addressed, including:

- Missing values in the data

- The effect of outliers

- Encoding categorical variables to numeric form

- Feature Scaling

- Feature Selection

Missing Values

The number of missing values in the data was extremely low, so instead of applying any imputation (i.e. mean, most common value) we will just remove those rows

# remove rows where values are missing

data_for_model.isna().sum()

data_for_model.dropna(how = "any", inplace = True)

Outliers

As KNN is a distance based algorithm, you could argue that if a data point is a long way away, then it will simply never be selected as one of the neighbours - and this is true - but outliers can still cause us problems here. The main issue we face is when we come to scale our input variables, a very important step for a distance based algorithm.

We don’t want any variables to be “bunched up” due to a single outlier value, as this will make it hard to compare their values to the other input variables. We should always investigate outliers rigorously - in this case we will simply remove them.

In this code section, just like we saw when applying Logistic Regression, we use .describe() from Pandas to investigate the spread of values for each of our predictors. The results of this can be seen in the table below.

| metric | distance_from_store | credit_score | total_sales | total_items | transaction_count | product_area_count | average_basket_value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mean | 2.61 | 0.60 | 968.17 | 143.88 | 22.21 | 4.18 | 38.03 |

| std | 14.40 | 0.10 | 1073.65 | 125.34 | 11.72 | 0.92 | 24.24 |

| min | 0.00 | 0.26 | 2.09 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 2.09 |

| 25% | 0.73 | 0.53 | 383.94 | 77.00 | 16.00 | 4.00 | 21.73 |

| 50% | 1.64 | 0.59 | 691.64 | 123.00 | 23.00 | 4.00 | 31.07 |

| 75% | 2.92 | 0.67 | 1121.53 | 170.50 | 28.00 | 5.00 | 46.43 |

| max | 400.97 | 0.88 | 7372.06 | 910.00 | 75.00 | 5.00 | 141.05 |

Again, based on this investigation, we see some max column values for several variables to be much higher than the median value.

This is for columns distance_from_store, total_sales, and total_items

For example, the median distance_to_store is 1.64 miles, but the maximum is over 400 miles!

Because of this, we apply some outlier removal in order to facilitate generalisation across the full dataset.

We do this using the “boxplot approach” where we remove any rows where the values within those columns are outside of the interquartile range multiplied by 2.

outlier_investigation = data_for_model.describe()

outlier_columns = ["distance_from_store", "total_sales", "total_items"]

# boxplot approach

for column in outlier_columns:

lower_quartile = data_for_model[column].quantile(0.25)

upper_quartile = data_for_model[column].quantile(0.75)

iqr = upper_quartile - lower_quartile

iqr_extended = iqr * 2

min_border = lower_quartile - iqr_extended

max_border = upper_quartile + iqr_extended

outliers = data_for_model[(data_for_model[column] < min_border) | (data_for_model[column] > max_border)].index

print(f"{len(outliers)} outliers detected in column {column}")

data_for_model.drop(outliers, inplace = True)

Split Out Data For Modelling

In exactly the same way we’ve done for the other three models, in the next code block we do two things, we firstly split our data into an X object which contains only the predictor variables, and a y object that contains only our dependent variable.

Once we have done this, we split our data into training and test sets to ensure we can fairly validate the accuracy of the predictions on data that was not used in training. In this case, we have allocated 80% of the data for training, and the remaining 20% for validation. Again, we make sure to add in the stratify parameter to ensure that both our training and test sets have the same proportion of customers who did, and did not, sign up for the delivery club - meaning we can be more confident in our assessment of predictive performance.

# split data into X and y objects for modelling

X = data_for_model.drop(["signup_flag"], axis = 1)

y = data_for_model["signup_flag"]

# split out training & test sets

X_train, X_test, y_train, y_test = train_test_split(X, y, test_size = 0.2, random_state = 42, stratify = y)

Categorical Predictor Variables

As we saw when applying the other algorithms, in our dataset, we have one categorical variable gender which has values of “M” for Male, “F” for Female, and “U” for Unknown.

The KNN algorithm can’t deal with data in this format as it can’t assign any numerical meaning to it when looking to assess the relationship between the variable and the dependent variable.

As gender doesn’t have any explicit order to it, in other words, Male isn’t higher or lower than Female and vice versa - one appropriate approach is to apply One Hot Encoding to the categorical column.

One Hot Encoding can be thought of as a way to represent categorical variables as binary vectors, in other words, a set of new columns for each categorical value with either a 1 or a 0 saying whether that value is true or not for that observation. These new columns would go into our model as input variables, and the original column is discarded.

We also drop one of the new columns using the parameter drop = “first”. We do this to avoid the dummy variable trap where our newly created encoded columns perfectly predict each other - and we run the risk of breaking the assumption that there is no multicollinearity, a requirement or at least an important consideration for some models, Linear Regression being one of them! Multicollinearity occurs when two or more input variables are highly correlated with each other, it is a scenario we attempt to avoid as in short, while it won’t neccessarily affect the predictive accuracy of our model, it can make it difficult to trust the statistics around how well the model is performing, and how much each input variable is truly having.

In the code, we also make sure to apply fit_transform to the training set, but only transform to the test set. This means the One Hot Encoding logic will learn and apply the “rules” from the training data, but only apply them to the test data. This is important in order to avoid data leakage where the test set learns information about the training data, and means we can’t fully trust model performance metrics!

For ease, after we have applied One Hot Encoding, we turn our training and test objects back into Pandas Dataframes, with the column names applied.

# list of categorical variables that need encoding

categorical_vars = ["gender"]

# instantiate OHE class

one_hot_encoder = OneHotEncoder(sparse=False, drop = "first")

# apply OHE

X_train_encoded = one_hot_encoder.fit_transform(X_train[categorical_vars])

X_test_encoded = one_hot_encoder.transform(X_test[categorical_vars])

# extract feature names for encoded columns

encoder_feature_names = one_hot_encoder.get_feature_names_out(categorical_vars)

# turn objects back to pandas dataframe

X_train_encoded = pd.DataFrame(X_train_encoded, columns = encoder_feature_names)

X_train = pd.concat([X_train.reset_index(drop=True), X_train_encoded.reset_index(drop=True)], axis = 1)

X_train.drop(categorical_vars, axis = 1, inplace = True)

X_test_encoded = pd.DataFrame(X_test_encoded, columns = encoder_feature_names)

X_test = pd.concat([X_test.reset_index(drop=True), X_test_encoded.reset_index(drop=True)], axis = 1)

X_test.drop(categorical_vars, axis = 1, inplace = True)

Feature Scaling

As KNN is a distance based algorithm, in other words it is reliant on an understanding of how similar or different data points are across different dimensions in n-dimensional space, the application of Feature Scaling is extremely important.

Feature Scaling is where we force the values from different columns to exist on the same scale, in order to enchance the learning capabilities of the model. There are two common approaches for this, Standardisation, and Normalisation.

Standardisation rescales data to have a mean of 0, and a standard deviation of 1 - meaning most datapoints will most often fall between values of around -4 and +4.

Normalisation rescales datapoints so that they exist in a range between 0 and 1.

The below code uses the in-built MinMaxScaler functionality from scikit-learn to apply Normalisation to all of our input variables. The reason we choose Normalisation over Standardisation is that our scaled data will all exist between 0 and 1, and these will then be compatible with any categorical variables that we have encoded as 1’s and 0’s.

In the code, we also make sure to apply fit_transform to the training set, but only transform to the test set. This means the scaling logic will learn and apply the scaling “rules” from the training data, but only apply them to the test data (or any other data we predict on in the future). This is important in order to avoid data leakage where the test set learns information about the training data, and means we can’t fully trust model performance metrics!

# create our scaler object

scale_norm = MinMaxScaler()

# normalise the training set (using fit_transform)

X_train = pd.DataFrame(scale_norm.fit_transform(X_train), columns = X_train.columns)

# normalise the test set (using transform only)

X_test = pd.DataFrame(scale_norm.transform(X_test), columns = X_test.columns)

Feature Selection

As we discussed when applying Logistic Regression above - Feature Selection is the process used to select the input variables that are most important to your Machine Learning task. For more information around this, please see that section above.

When applying KNN, Feature Selection is an interesting topic. The algorithm is measuring the distance between data-points across all dimensions, where each dimension is one of our input variables. The algorithm treats each input variable as equally important, there isn’t really a concept of “feature importance” so the spread of data within an unimportant variable could have an effect on judging other data points as either “close” or “far”. If we had a lot of “unimportant” variables in our data, this could create a lot of noise for the algorithm to deal with, and we’d just see poor classification accuracy without really knowing why.

Having a high number of input variables also means the algorithm has to process a lot more information when processing distances between all of the data-points, so any way to reduce dimensionality is important from a computational perspective as well.

For our task here we are again going to apply Recursive Feature Elimination With Cross Validation (RFECV) which is an approach that starts with all input variables, and then iteratively removes those with the weakest relationships with the output variable. RFECV does this using Cross Validation, so splits the data into many “chunks” and iteratively trains & validates models on each “chunk” seperately. This means that each time we assess different models with different variables included, or eliminated, the algorithm also knows how accurate each of those models was. From the suite of model scenarios that are created, the algorithm can determine which provided the best accuracy, and thus can infer the best set of input variables to use!

# instantiate RFECV & the model type to be utilised

from sklearn.ensemble import RandomForestClassifier

clf = RandomForestClassifier(random_state = 42)

feature_selector = RFECV(clf)

# fit RFECV onto our training & test data

fit = feature_selector.fit(X_train,y_train)

# extract & print the optimal number of features

optimal_feature_count = feature_selector.n_features_

print(f"Optimal number of features: {optimal_feature_count}")

# limit our training & test sets to only include the selected variables

X_train = X_train.loc[:, feature_selector.get_support()]

X_test = X_test.loc[:, feature_selector.get_support()]

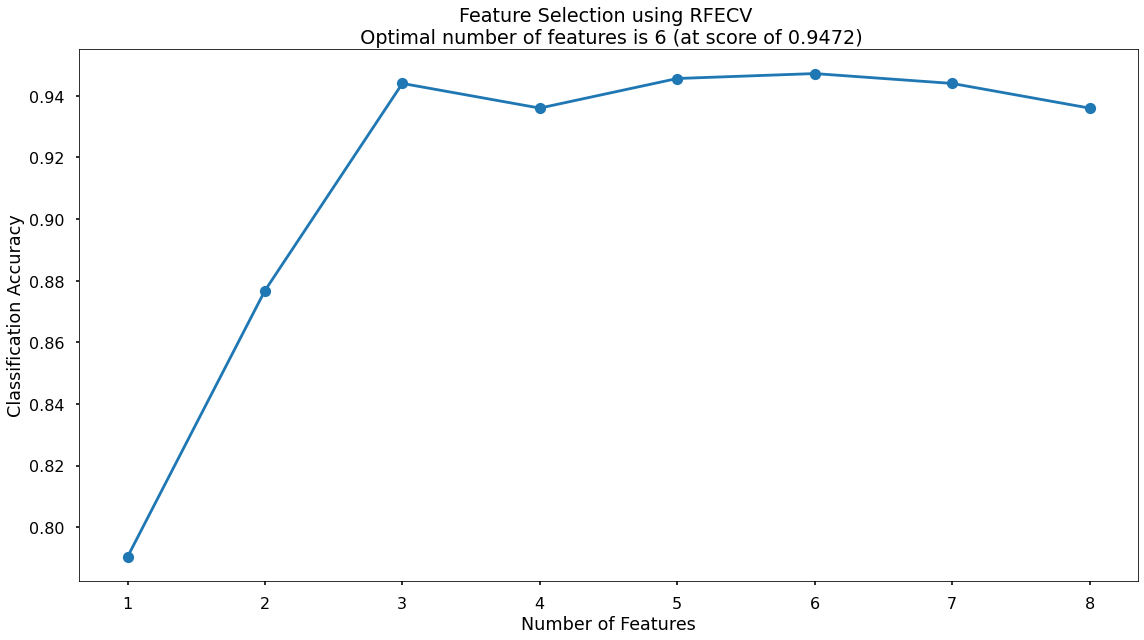

The below code then produces a plot that visualises the cross-validated classification accuracy with each potential number of features

plt.style.use('seaborn-poster')

plt.plot(range(1, len(fit.cv_results_['mean_test_score']) + 1), fit.cv_results_['mean_test_score'], marker = "o")

plt.ylabel("Classification Accuracy")

plt.xlabel("Number of Features")

plt.title(f"Feature Selection using RFECV \n Optimal number of features is {optimal_feature_count} (at score of {round(max(fit.cv_results_['mean_test_score']),4)})")

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

This creates the below plot, which shows us that the highest cross-validated classification accuracy (0.9472) is when we include six of our original input variables - although there isn’t much difference in predictive performance between using three variables through to eight variables - and this syncs with what we saw in the Random Forest section above where only three of the input variables scored highly when assessing Feature Importance & Permutation Importance.

The variables that have been dropped are total_items and credit score - we will continue on with the remaining six!

Model Training

Instantiating and training our KNN model is done using the below code. At this stage we will just use the default parameters, meaning that the algorithm:

- Will use a value for k of 5, or in other words it will base classifications based upon the 5 nearest neighbours

- Will use uniform weighting, or in other words an equal weighting to all 5 neighbours regardless of distance

# instantiate our model object

clf = KNeighborsClassifier()

# fit our model using our training & test sets

clf.fit(X_train, y_train)

Model Performance Assessment

Predict On The Test Set

To assess how well our model is predicting on new data - we use the trained model object (here called clf) and ask it to predict the signup_flag variable for the test set.

In the code below we create one object to hold the binary 1/0 predictions, and another to hold the actual prediction probabilities for the positive class (which is based upon the majority class within the k nearest neighbours)

# predict on the test set

y_pred_class = clf.predict(X_test)

y_pred_prob = clf.predict_proba(X_test)[:,1]

Confusion Matrix

As we’ve seen with all models so far, our Confusion Matrix provides us a visual way to understand how our predictions match up against the actual values for those test set observations.

The below code creates the Confusion Matrix using the confusion_matrix functionality from within scikit-learn and then plots it using matplotlib.

# create the confusion matrix

conf_matrix = confusion_matrix(y_test, y_pred_class)

# plot the confusion matrix

plt.style.use("seaborn-poster")

plt.matshow(conf_matrix, cmap = "coolwarm")

plt.gca().xaxis.tick_bottom()

plt.title("Confusion Matrix")

plt.ylabel("Actual Class")

plt.xlabel("Predicted Class")

for (i, j), corr_value in np.ndenumerate(conf_matrix):

plt.text(j, i, corr_value, ha = "center", va = "center", fontsize = 20)

plt.show()

The aim is to have a high proportion of observations falling into the top left cell (predicted non-signup and actual non-signup) and the bottom right cell (predicted signup and actual signup).

The results here are interesting - all of the errors are where the model incorrectly classified delivery club signups as non-signups - the model made no errors when classifying non-signups non-signups.

Since the proportion of signups in our data was around 30:70 we will next analyse not only Classification Accuracy, but also Precision, Recall, and F1-Score which will help us assess how well our model has performed in reality.

Classification Performance Metrics

Accuracy, Precision, Recall, F1-Score

For details on these performance metrics, please see the above section on Logistic Regression. Using all four of these metrics in combination gives a really good overview of the performance of a classification model, and gives us an understanding of the different scenarios & considerations!

In the code below, we utilise in-built functionality from scikit-learn to calculate these four metrics.

# classification accuracy

accuracy_score(y_test, y_pred_class)

# precision

precision_score(y_test, y_pred_class)

# recall

recall_score(y_test, y_pred_class)

# f1-score

f1_score(y_test, y_pred_class)

Running this code gives us:

- Classification Accuracy = 0.936 meaning we correctly predicted the class of 93.6% of test set observations

- Precision = 1.00 meaning that for our predicted delivery club signups, we were correct 100% of the time

- Recall = 0.762 meaning that of all actual delivery club signups, we predicted correctly 76.2% of the time

- F1-Score = 0.865

These are interesting. The KNN has obtained the highest overall Classification Accuracy & Precision, but the lower Recall score has penalised the F1-Score meaning that is actually lower than what was seen for both the Decision Tree & the Random Forest!

Finding The Optimal Value For k

By default, the KNN algorithm within scikit-learn will use k = 5 meaning that classifications are based upon the five nearest neighbouring data-points in n-dimensional space.

Just because this is the default threshold does not mean it is the best one for our task.

Here, we will test many potential values for k, and plot the Precision, Recall & F1-Score, and find an optimal solution!

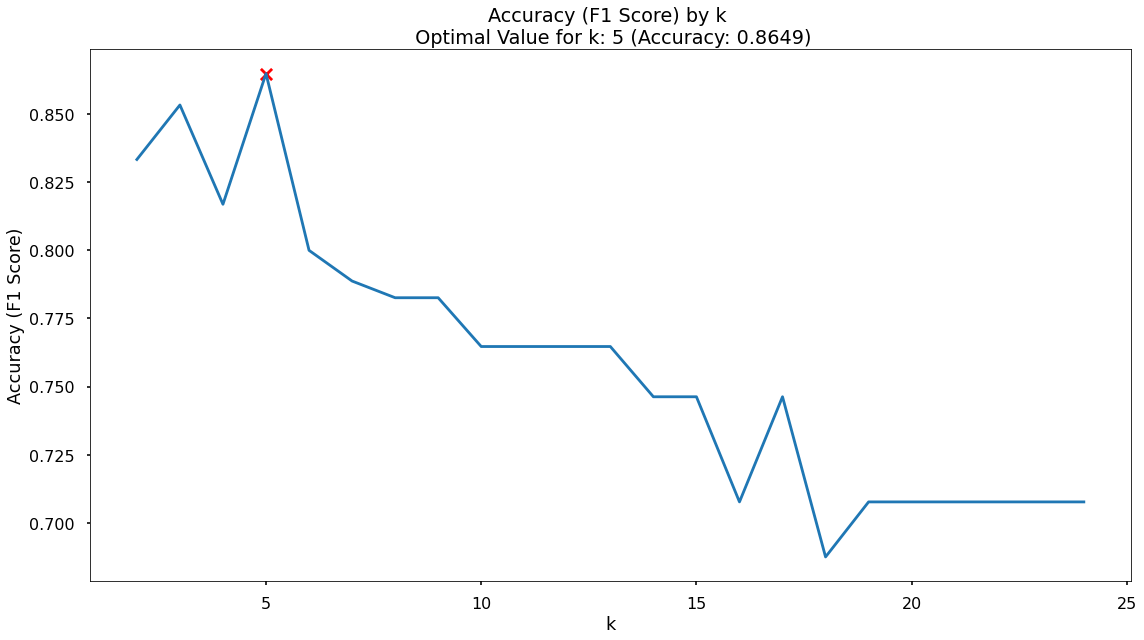

# set up range for search, and empty list to append accuracy scores to

k_list = list(range(2,25))

accuracy_scores = []

# loop through each possible value of k, train and validate model, append test set f1-score

for k in k_list:

clf = KNeighborsClassifier(n_neighbors = k)

clf.fit(X_train,y_train)

y_pred = clf.predict(X_test)

accuracy = f1_score(y_test,y_pred)

accuracy_scores.append(accuracy)

# store max accuracy, and optimal k value

max_accuracy = max(accuracy_scores)

max_accuracy_idx = accuracy_scores.index(max_accuracy)

optimal_k_value = k_list[max_accuracy_idx]

# plot accuracy by max depth

plt.plot(k_list,accuracy_scores)

plt.scatter(optimal_k_value, max_accuracy, marker = "x", color = "red")

plt.title(f"Accuracy (F1 Score) by k \n Optimal Value for k: {optimal_k_value} (Accuracy: {round(max_accuracy,4)})")

plt.xlabel("k")

plt.ylabel("Accuracy (F1 Score)")

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

That code gives us the below plot - which visualises the results!

In the plot we can see that the maximum F1-Score on the test set is found when applying a k value of 5 - which is exactly what we started with, so nothing needs to change!

Modelling Summary

The goal for the project was to build a model that would accurately predict the customers that would sign up for the delivery club. This would allow for a much more targeted approach when running the next iteration of the campaign. A secondary goal was to understand what the drivers for this are, so the client can get closer to the customers that need or want this service, and enhance their messaging.

Based upon these, the chosen the model is the Random Forest as it was a) the most consistently performant on the test set across classication accuracy, precision, recall, and f1-score, and b) the feature importance and permutation importance allows the client an understanding of the key drivers behind delivery club signups.

Metric 1: Classification Accuracy

- KNN = 0.936

- Random Forest = 0.935

- Decision Tree = 0.929

- Logistic Regression = 0.866

Metric 2: Precision

- KNN = 1.00

- Random Forest = 0.887

- Decision Tree = 0.885

- Logistic Regression = 0.784

Metric 3: Recall

- Random Forest = 0.904

- Decision Tree = 0.885

- KNN = 0.762

- Logistic Regression = 0.69

Metric 4: F1 Score

- Random Forest = 0.895

- Decision Tree = 0.885

- KNN = 0.865

- Logistic Regression = 0.734

Application

We now have a model object, and a the required pre-processing steps to use this model for the next delivery club campaign. When this is ready to launch we can aggregate the neccessary customer information and pass it through, obtaining predicted probabilities for each customer signing up.

Based upon this, we can work with the client to discuss where their budget can stretch to, and contact only the customers with a high propensity to join. This will drastically reduce marketing costs, and result in a much improved ROI.

Growth & Next Steps

While predictive accuracy was relatively high - other modelling approaches could be tested, especially those somewhat similar to Random Forest, for example XGBoost, LightGBM to see if even more accuracy could be gained.

We could even look to tune the hyperparameters of the Random Forest, notably regularisation parameters such as tree depth, as well as potentially training on a higher number of Decision Trees in the Random Forest.

From a data point of view, further variables could be collected, and further feature engineering could be undertaken to ensure that we have as much useful information available for predicting customer loyalty